White papers could be produced with new bleaching techniques, and sizes such as gelatine influenced the absorption. For instance, a hard sized paper could withstand the more experimental and often harsh treatments of the artist at work. During the finishing processes of the paper, surface texture could be imparted. These fell into three categories: ‘Hot pressed’ (HP) for detailed work; ‘rough’ (unpressed) for sketching; and ‘Not’ (not hot pressed) for less precise work.

During any restoration or conservation of a work of art, knowledge of the paper production can be important for the treatment. As paper ages, many factors related to its production process can contribute to its weakening. Chemical residues from the bleaching of the paper pulp, metal particles from the machinery as well as certain sizes which were added into paper can cause it to become brittle and discoloured and encourage some of the foxing which we commonly see today.

As the papers were often attached to a watercolour board to provide the outdoor artist with a firm surface to work on, this can cause difficulties when treatment is required. Sometimes the watercolour must be removed from the board for treatment to take place; once treatment is complete, however, a painting can be re-mounted to recreate the original format.

Painting Techniques

The watercolour handbooks of the nineteenth century offered many suggestions to the artist on how to achieve certain effects. These ranged from sponging, scraping or wiping off the applied paint to abrading or scratching (known as ‘scrapping out’) into the paper. The artist, John Mallord William Turner (1775-1851) is well-known for using a variety of techniques to ensure the paint and papers were manipulated to produce his desired effects. Often generously laying the paint down, Turner would famously scrape, sponge, wash and wipe his paintings.

There were many handbooks on watercolour painting and artists experimented widely with their recommended techniques. Skies were to be painted very wet and the paint then sponged out; trees were to receive a glaze before detail was added; and paper could by dyed with tea or coffee to give a background hue.

When a painting is being restored, conservators are always alert to expecting the unexpected and must pay close attention to any element of the painting that could be mistaken for damage.

When possible, it helps to have knowledge of the artist’s preferred technique. In the absence of this, a good knowledge of art history and the materials used can be invaluable.

Pigments

There were many new pigments invented and discovered during the nineteenth century and handbooks guided the watercolour artist to the most appropriate pigments for use in landscape painting. Cobalt blue with a wash of lamp black was good for clouds, Prussian blue and gamboge (yellow) was the favourite for foliage and ochre and lake were suggested for mountains.

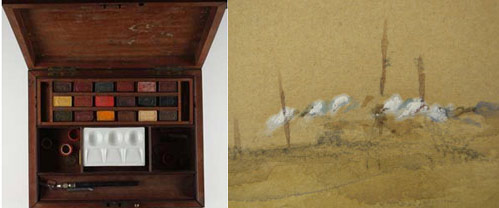

With the rise of the amateur painter and the popularity of painting outdoors, carrying cases for paint became essential. These culminated in the ‘shilling colour box’, a Victorian paint tin introduced in the 1830’s. These watercolours required only the addition of a little water, making them much faster to use than the more laborious dry predecessors which had required grinding. By 1846, watercolour paint could be bought in small metal tubes which had ingredients such as honey and gum Arabic added to aid the flow and drying times of the paint. As many artists had begun to paint outdoors, these new inventions offered more flexibility in location. Influenced by the outdoor light, such landscapes came to be typified by the recurrent use of blues, browns and sharp light falling on the scene.

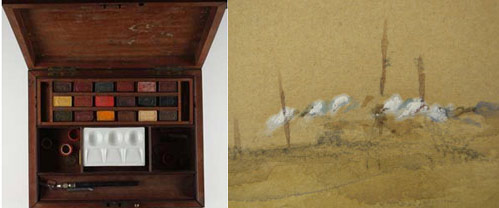

Pigments, of course, can fade or alter their colour dramatically over time in response to daylight, electric light, humidity or poor storage and mounting practices. As the paper’s support ages, its acidity can also increase, which can cause pigments to change their hue. A blue, for instance, can often turn to a buff colour. Another aging issue can be seen with zinc white, a common pigment that was often used for highlights. While it has always maintained an excellent watercolour permanence rating, it degrades the paper surrounding it, causing localised browning and increases the absorbance of ultraviolet light rays.

Victorian wooden paint box, complete with paint pans and a ceramic mixing palette.

Thickly applied zinc white paint highlights this washing blowing on a line, (detail from a painting by William George Horton, 1859-1950)

During painting conservation treatment, conservators always consider which pigments may be present. Their identification can influence the proposed treatment and the aftercare advice given on storage and display methods.

In summary, the development of watercolour painting during the nineteenth century is part of a fascinating and complex web of science, art and ingenuity set against a backdrop of great social and political change. Conservators take into account that watercolour paintings are composite

Victorian wooden paint box, complete with paint pans and a ceramic mixing palette.

Thickly applied zinc white paint highlights this washing blowing on a line, (detail from a painting by William George Horton, 1859-1950)

objects, made of paper, pigments, glues, binders and techniques. Careful treatment of these will conserve not only the paintings themselves but also a window into the nineteenth century, an era which has shaped our modern day world.

Zoe Finlay

2012